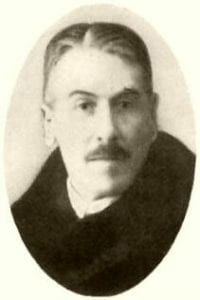

Dinosaur fossils were surely unearthed in Haţeg for centuries, but it was not until the late 19th century that they came to the attention of the scientific community, thanks to the work of a Hungarian aristocrat turned palaeontologist, Baron Franz Nopcsa (1877-1933).

Early Excavations

Franz Nopcsa’s passion for the Haţeg dinosaurs was sparked when in 1895 a number of dinosaur bones were found by his sister Ilona at Sânpetru (or Szentpéterfalva) near the family estate at Sãcel (also called Szacsal) in Transylvania, which was at that time part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, but is now part of western Romania. He brought the bones to Vienna in the hopes of having them identified but was advised by the Professor of Geology Eduard Suess that he should undertake his own study . Two years later when Nopcsa was only twenty he published his first paper (Nopcsa 1897) and it was in this same year that he began his studies at Vienna University.

Nopcsa’s passion for geology and palaeontology, especially that of the Haţeg area, never waned and his early notable accomplishments include the naming of the Szentpéterfalva (Sânpetru) sandstone as a stratigraphic unit and the beginning of his systematic description of the dinosaurs of the Haţeg basin in the first of five monographs (Nopcsa 1900, 1902, 1904, 1928, 1929). published as ‘Dinosaurierreste aus Siebenbürgen’ (‘Dinosaur remains from Transylvania’).

Nopcsa was first to suggest that the small dinosaur specimens he had found were island dwarves at a meeting in Vienna in November 1912. Nopcsa (1914b) wrote that “while the turtles, crocodilians and similar animals of the Late Cretaceous reached their normal size, the dinosaurs almost always remain below their normal size.” He observed that most of the Transylvanian dinosaurs hardly reached 4 m in length and, for the largest (what was to become Magyarosaurus dacus), it was a puny 6 m long compared to the usual size of 15-20 m for related sauropods.

Nopcsa’s contribution to the understanding of Palaeontology were later sumarised by Grigorescu (2005):

- Systematic Palaeontology: description of 9 species of dinosaurs and other fossil reptiles, out of which 6 were confirmed by the subsequent revisions;

- Chronostratigraphy and Geological mapping: dating the continental fossiliferous deposits as Danian, at that time considered the uppermost stage of the Cretaceous; first detailed geological map of the Haţeg Basin and the neighbouring regions, with the Upper Cretaceous marine deposits clearly delimited from the overlaying continental deposits with dinosaur remains, the latter being described under the generic name of ‘Sânpetru sandstone’;

- Evolution: recognition of the primitiveness of most of the taxa from the Haţeg palaeofauna, stressing that in spite of their chronostratigraphic position at the end of the Upper Cretaceous, many of them much closely related to Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous taxa;

- Palaeobiology: besides their primitiveness, many species from the Haţeg palaeofauna were much smaller than their closest relatives from other regions of Europe. Both the primitiveness and the small size were explained by Nopcsa by the isolated condition, on an island, in which the dinosaurs and their other co-habitants lived for a long span of time; this biological phenomenon, common for large animals living in small and medium-sized islands is known as ‘island dwarfing’.

After Nopcsa’s work, there were few investigations in the Haţeg area. These included studies of the geology, leading to the discovery of some interesting fossilised bones (Mamulea, 1953a, b) and plants (Mãrgãrit and Mãrgãrit, 1967), but also caused controversy regarding the age of the continental deposits with dinosaur remains. After the work of Mamulea (1953a, b), a large part of Nopcsa’s Danian deposits were assigned to different stages of the Palaeogene, and the dinosaur bones were seen as redeposited from older beds. The late Cretaceous age of the Haţeg Basin and Nopcsa’s dinosaurs was confirmed by Dincã et al. (1972).

Modern Resurgence

Left: Dan Grigorescu, photo courtesy of the University of Bucharest

Left: Dan Grigorescu, photo courtesy of the University of Bucharest

From 1977 onwards Dan Grigorescu of the University of Bucharest organised yearly summer camps for geology students, with the main aim of finding ‘fossiliferous pockets’ and to excavate them. The first few years focused on the Sibisel valley, were Nopsca found many bones, but focus soon turned to a much wider area. An important contributer to the expansion of the fossil record came from Ioan Groza of the Museum in Deva (capital of Hunedoara county, in which Haţeg is located).This proximity to the fossiliferous deposits allowed Groza to continue the excavations during the autumn, after Grigorescu and his students from Bucharest had left. These excavations were supplemented by micropalaeontological studies, which led to a great increase in the number and variety of vertebrate taxa (Grigorescu 2010).

Today Haţeg is one of the best studied late Cretaceous dinosaur sites. An unusual feature of the dinosaurs is that they are tiny, which has led many to conclude that these were island dwarves.

Literature cited

- Dincã, A., Tocorjescu, M., and Stilla, A. 1972. Despre vârsta depozitelor continentale cu dinozaurieni din Bazinele Haţeg ci Rusca Montanã. Dãri de Seamã ale Institutului Geologic Român 58, 83-94.

- Grigorescu D. 2005. Rediscovery of a ‘forgotten land’. The last three decades of research on the dinosaur-bearing deposits from the Haţeg Basin. Acta Palaeontologica Romaniae 5, 191-204.

- Grigorescu, D. 2010. The Latest Cretaceous fauna with dinosaurs and mammals from the Haţeg Basin – a historical overview. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 293, 271-282.

- Mamulea, M.A. 1953a. Cercetãri geologice în partea de Vest a Bazinului Haţeg (Regiunea Sarmisegetuza – Rãchitova). Dãri de Seamã ale Comitetului Geologic Român 37, 142-148.

- Mamulea, M.A. 1953b. Studii geologice în regiunea Sânpetru – Pui (Bazinul Haţegului). Anuarul Comitetului Geologic Român 25, 211-274.

- Mãrgãrit, G. and Mãrgãrit, M. 1967. Asupra prezentei unor resturi de plante fosile în împrejurimile localitãtii Densus (Bazinul Haţeg). Studii Cercetãri de Geologie, Geofizicã Geografie, Geologie 12, 471-476.

- Nopcsa, F. 1897. Vorläufiger Bericht über das Auftreten von oberer Kreide im Hátszeger Thale in Siebenbürgen. Verhandlungen der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Akademie des Wissenschaften 1897, 273-274.

- Nopcsa, F. 1900. Dinosaurierreste aus Siebenbürgen I. Schädel von Limnosaurus transsylvanicus nov. gen. et nov. spec. Denkschriften der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Klasse 68, 555-591.

- Nopcsa, F. 1902. Dinosaurierreste aus Siebenbürgen II. (Schädelreste von Mochlodon). Mit einem Anhange: zur Phylogenie der Ornithopodiden. Denkschriften der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Klasse 72, 149-175.

- Nopcsa, F. 1904. Dinosaurierreste aus Siebenbürgen III.Weitere Schädelreste vonMochlodon. Denkschriften der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Klasse 74, 229-263.

- Nopcsa, F. 1914a. Die Lebensbedingungen der obercretacischen Dinosaurier Siebenbürgens. Centralbaltt für Mineralogie, Geologie, und Paläontologie 1914, 564-574.

- Nopcsa, F. 1914b. Über das Vorkommen der Dinosaurier in Siebenbürgen. Verhandlungen der zoologische-botanischen Gesellschaft, Wien 54, 12-14.

- Nopcsa, F. 1928. Dinosaurierreste aus Siebenbürgen IV. Wirbelsaule von Rhabdodon und Orthomerus. Palaeontologia Hungarica 1, 273-304.

- Nopcsa, F. 1929. Dinosaurierreste aus Siebenbürgen V. Geologica Hungarica, Ser. Palaeontologica 4, 1-76.